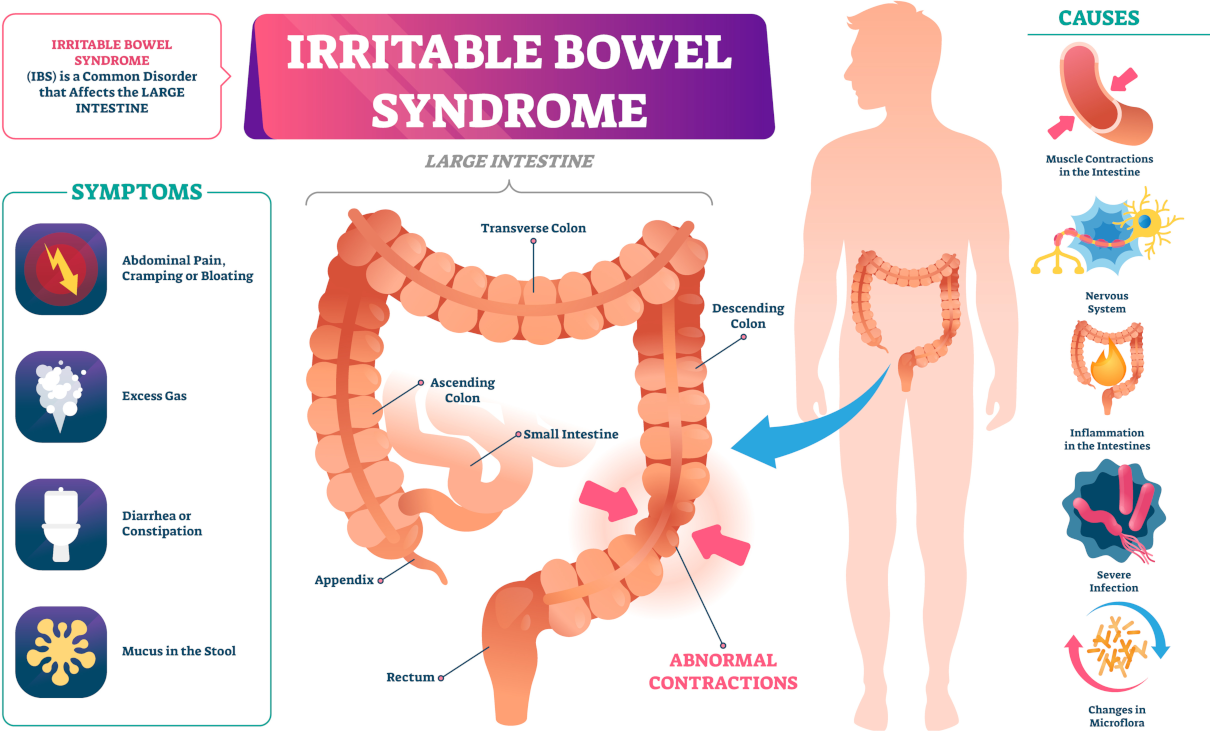

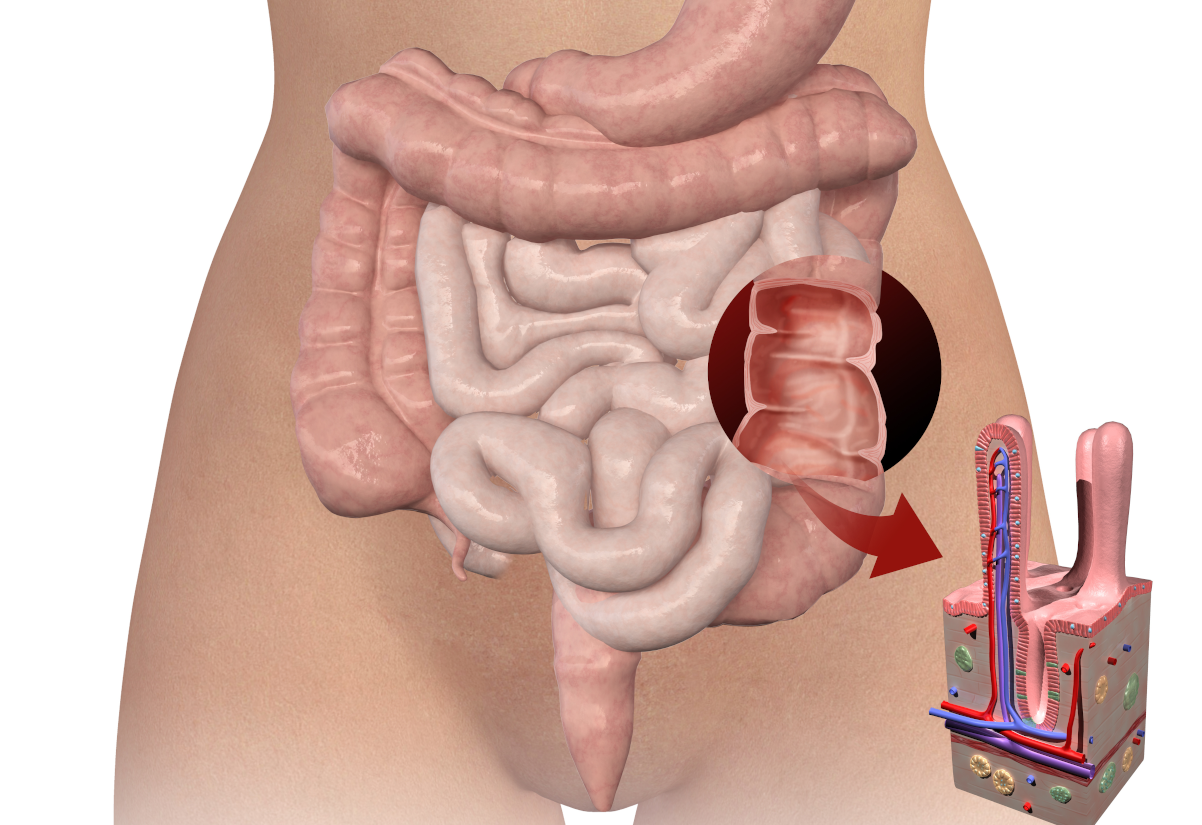

The large intestine is part of the alimentary tract extending from the ileocecal valve to the anus. It is approximately five feet long and has an average diameter of 2 1/2 inches. The large intestine has five regions: the cecum, ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid colon. The cecum is a blind pouch that receives chyme from the ileum through the ileocecal valve. It has the largest diameter (3 to 3.5 inches) of the large intestine and is the least motile, but it does occur in various abdominal positions.

The ascending colon, approximately 8 inches long, arises from the cecum on the right side of the abdomen and extends upwards to a position behind the liver. It curves to the left at the hepatic flexure and becomes the transverse colon (approximately 16-20 inches long), extending across the abdomen. This region exhibits the most colonic movement. It extends inferiorly at the splenic flexure to the level of the iliac crest. It is descending (approximately 10-12 inches long). The colon turns toward the midline at the iliac crest in a form resembling the letter S. This turning point is the sigmoid flexure, and the region is that of the sigmoid colon (approximately 16 inches long).

The sigmoid colon empties into the last part of the large intestine, the rectum (approximately 4 to 7 inches long). Three semilunar valves (Valves of Houston) are present in the mucosal layer of the rectum, slowing faecal movement through this region. The rectum is not designed to serve as a reservoir but typically is empty unless defecation occurs. Generally, the descending and sigmoid colons evacuate at the same time.

Currently, we only offer colonic services in London.

We refer to the last two to three inches of the rectum as the anal canal. Its lining is not of mucus but squamous epithelium. Several blood vessels are present in this region, and their inflammation is known as piles or haemorrhoids. An external sphincter muscle is located at the distal end of the canal, and an internal sphincter is at its proximal end. The former is under voluntary control, while the latter is an involuntary muscle. Levator ani muscles assist the above sphincters during defecation.

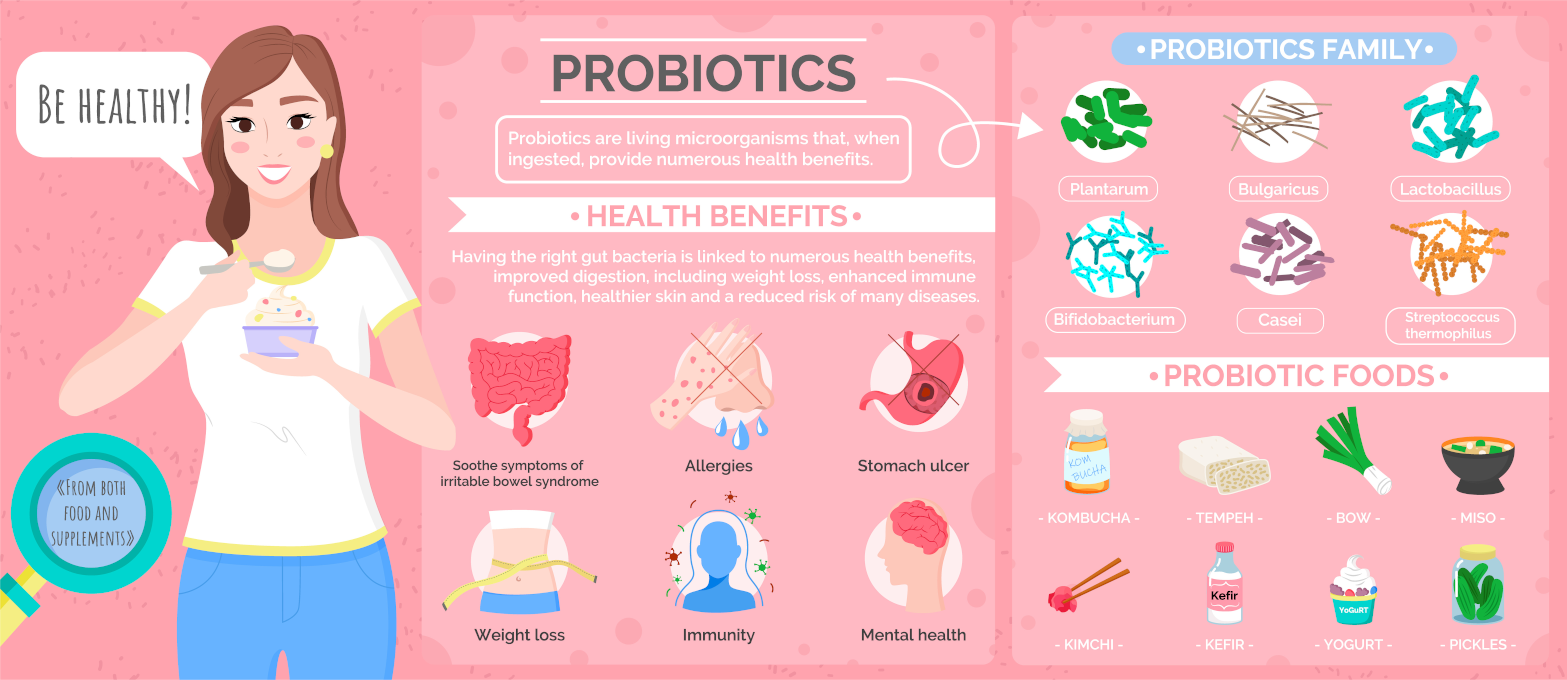

Mini Detox PLUS – 3 colonics, minerals, herbal & probiotic implants

The ideal pattern of colonic treatments includes three alkalising colon hydrotherapy treatments with sodium bicarbonate, one anti-parasitic implant on the first treatment, one liver and gall bladder stimulating herbal implant on the second treatment, and a high-strength probiotic implant on the third colonic.

Large intestine and different organs

Intestinal movements are of four types: haustral churning, peristalsis, mass peristalsis, and antiperistalsis. Also, haustral churning involves a haustrum’s filling, distension and contraction. It moves chyme from one haustrum to the next. Peristalsis is the slow, wavelike contractions of the longitudinal and circular muscles. It also aids in the forward movement of the chyme. Mass peristalsis refers to muscular peristaltic contractions in the sigmoid colon. Thus, it pushes its contents into the rectum before defecation.

Bastedo and others have observed a rare yet fourth type of intestinal movement. Hypothetically, it holds back colon contents for a while to absorb nutrients in the cecum, ascending colon, and small intestine. The large intestine is more expansive in diameter. It contains several “pockets” (haustra) and more longitudinal muscle bands (Taeniae coli). The small intestine has villi and plicae circulares, which are absent in the large intestine.

Most digestion and absorption are complete when the chyme reaches the cecum. The primary function of the large intestine is the formation and elimination of faeces. Faeces consist of undigested food residues, intestinal epithelium and mucus, bacteria, and water. Ranklin, Bargen, and Buie consider the colon divisible into right and left halves. The right portion is concerned with digestion and absorption, while the left is concerned with storing intestinal debris. The ileocecal valve permits unabsorbed material to enter the cecum. Moreover, it prevents colon bacteria from entering the ileum.

Food intolerance test of 208 ingredients

This one is our most comprehensive food and drink test. The test analyses your client’s IgG antibody reactions to 208 food and drink ingredients. This test will highlight their food triggers and help you formulate an IgG-guided elimination diet together.

Colon bacteria

Colon bacteria ferment starches, releasing hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane gases, converting any leftover protein into amino acids. These products then convert to indoles and hydrogen sulfide, which give the faeces its odour. Bilirubin, which enters the intestine in the bile, is broken down into other pigments by bacteria and is responsible for the normal colouration of wastes (i.e., brown). Light, clay-coloured stools indicate a biliary deficiency or blockage. The amount, composition, colour and odour of faeces depend on the food ingested.

A diet of many vegetables will produce many excrements, generally dark yellow. A high protein diet will create a small amount of very dark faeces. In a mixed diet, the bulk will vary, but the faeces should generally be brown. Black stools indicate upper intestinal pathology. The black is from the blood traversing a long distance through the intestine.

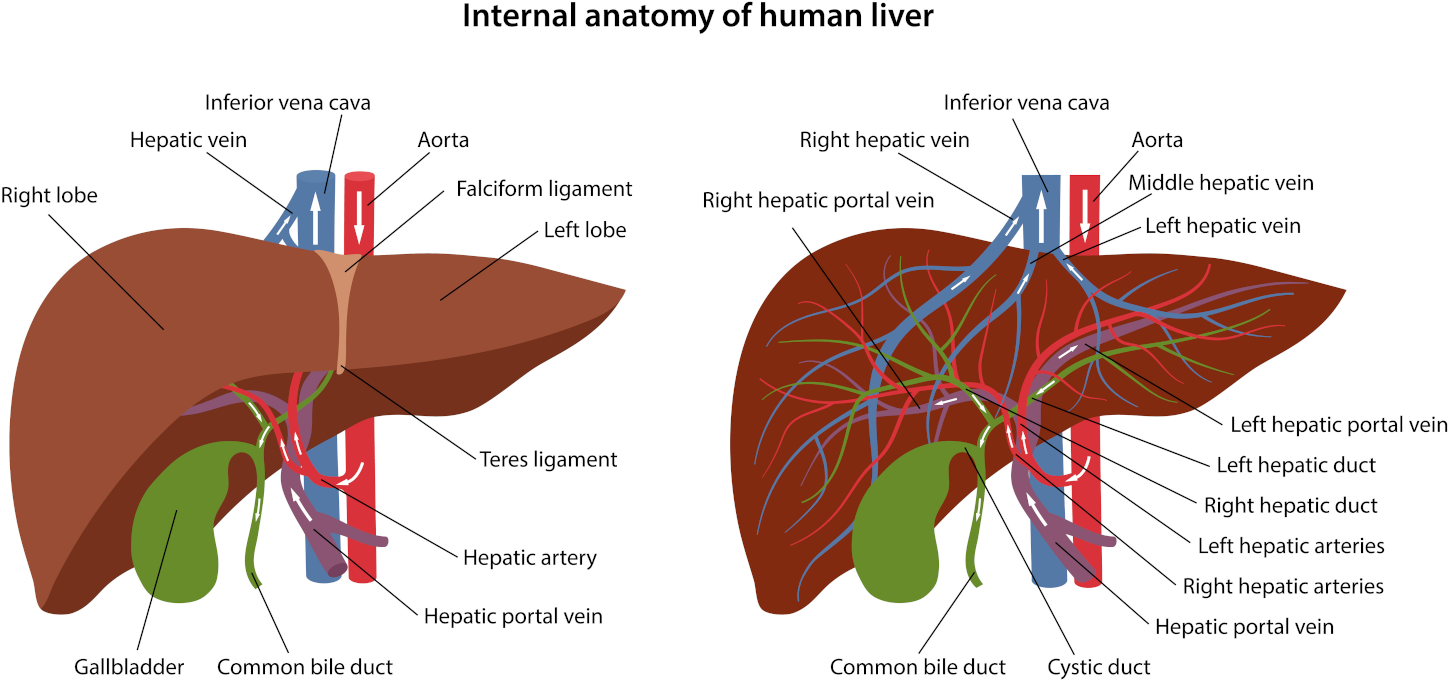

Bacteria also produce several essential vitamins, which are absorbed by the large intestine and stored in the liver (K and B vitamins). Besides vitamins, the colon absorbs large amounts of water (cecum and ascending colon). Unfortunately, toxins from bacterial metabolism can also enter the bloodstream without hindrance. These (indol, skatol, cresol, phenol and others) are treated by the liver and excreted by the kidneys.

Our body excretes hydrogen and methane gasses absorbed in the colon through the lungs. Thus, very foul breath is often a symptom of a stagnant and fermenting colon. Besides lubrication, mucus is secreted by the large bowel to prevent the entrance of toxins into the blood mechanically.

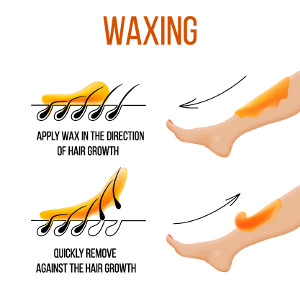

Bum waxing(outside only or inside only) using hot beeswax

Skilled practitioners and high-quality materials allow you to achieve a high-quality effect without irritation and allergic reactions. Buttock epilation is an aesthetic method of removing unwanted hairs in the delicate area of the female body. This treatment lasts fifteen minutes.