Scientists have found the mechanism of immunity suppression by a coronavirus in the human body.

An article in the bioRxiv e-library describes that molecular biologists in Germany have discovered something important. So, when it enters the intestinal cells, the coronavirus blocks the work of genes associated with the function of innate immunity and the production of interferons. Interferons are antiviral protein molecules.

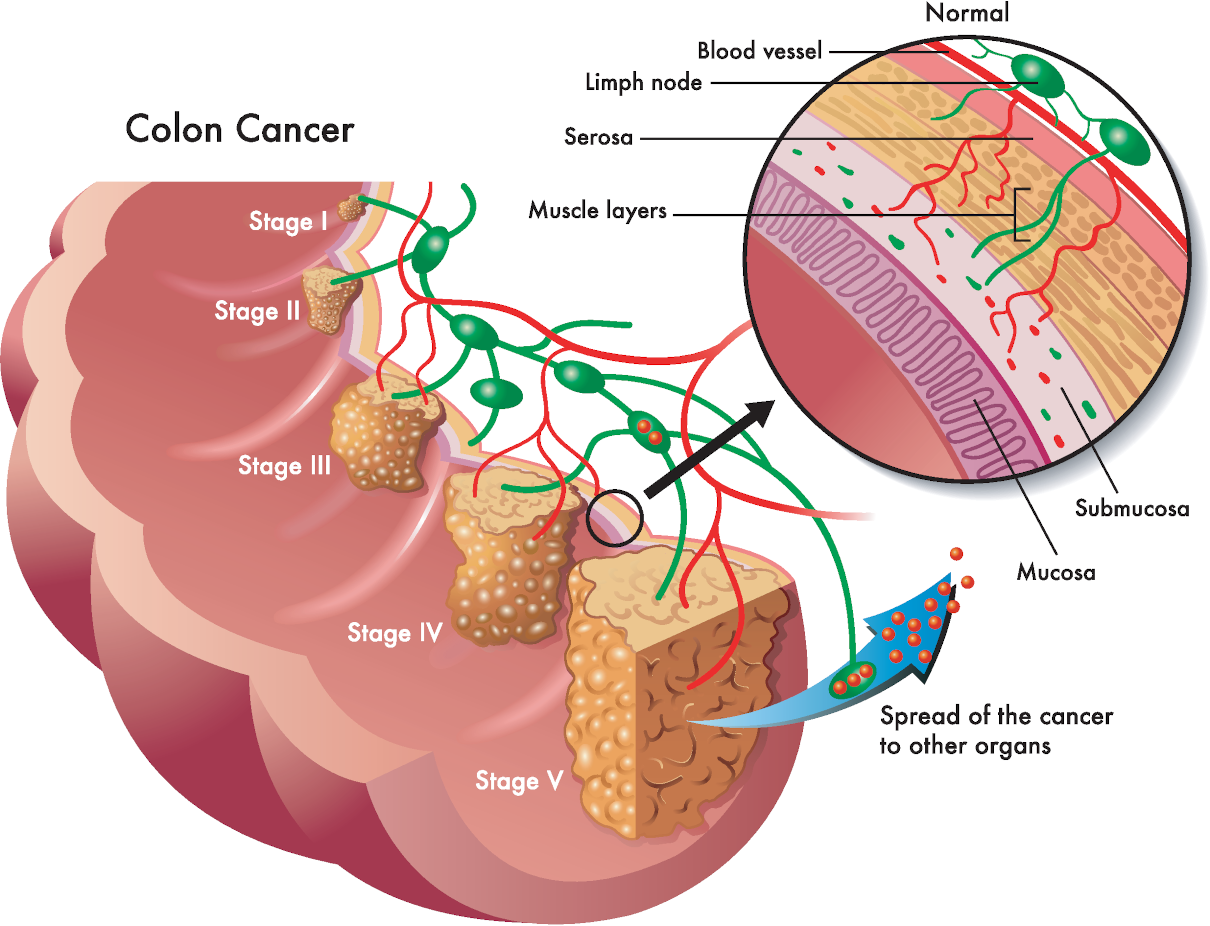

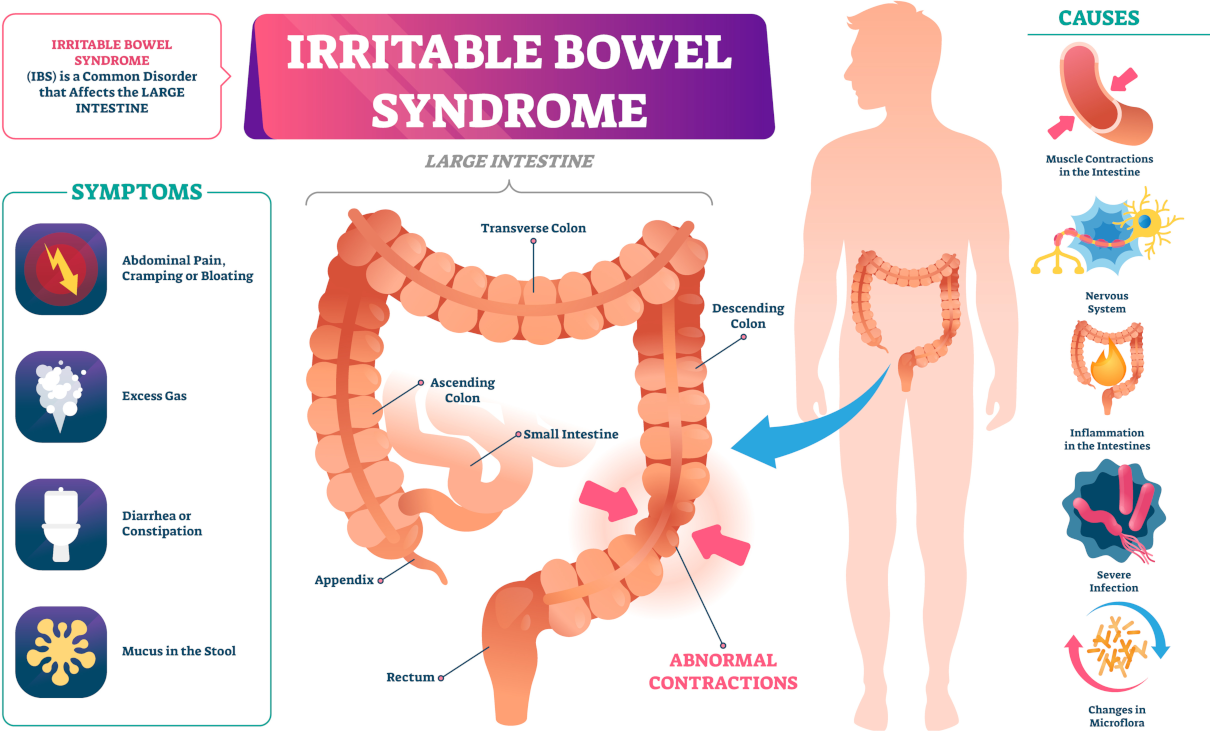

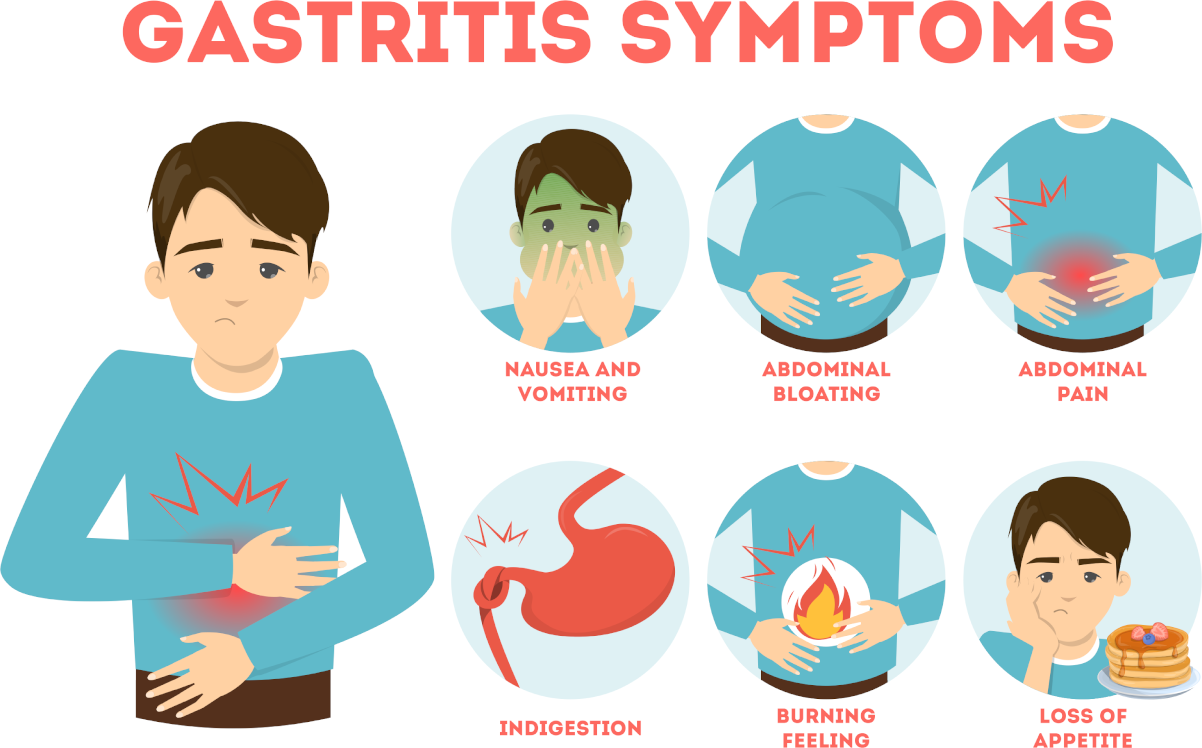

“Our experiments indicate that the SARS-CoV-2 virus suppresses the immune response in immature enterocytes, the primary cells of the human intestine. That allows the virus to multiply in them and spread throughout the body. It also turns the digestive system into a reservoir of inflammation. Therefore, we must study it for a full understanding of the pathogenesis of coronavirus infection,” reads the text of the study.

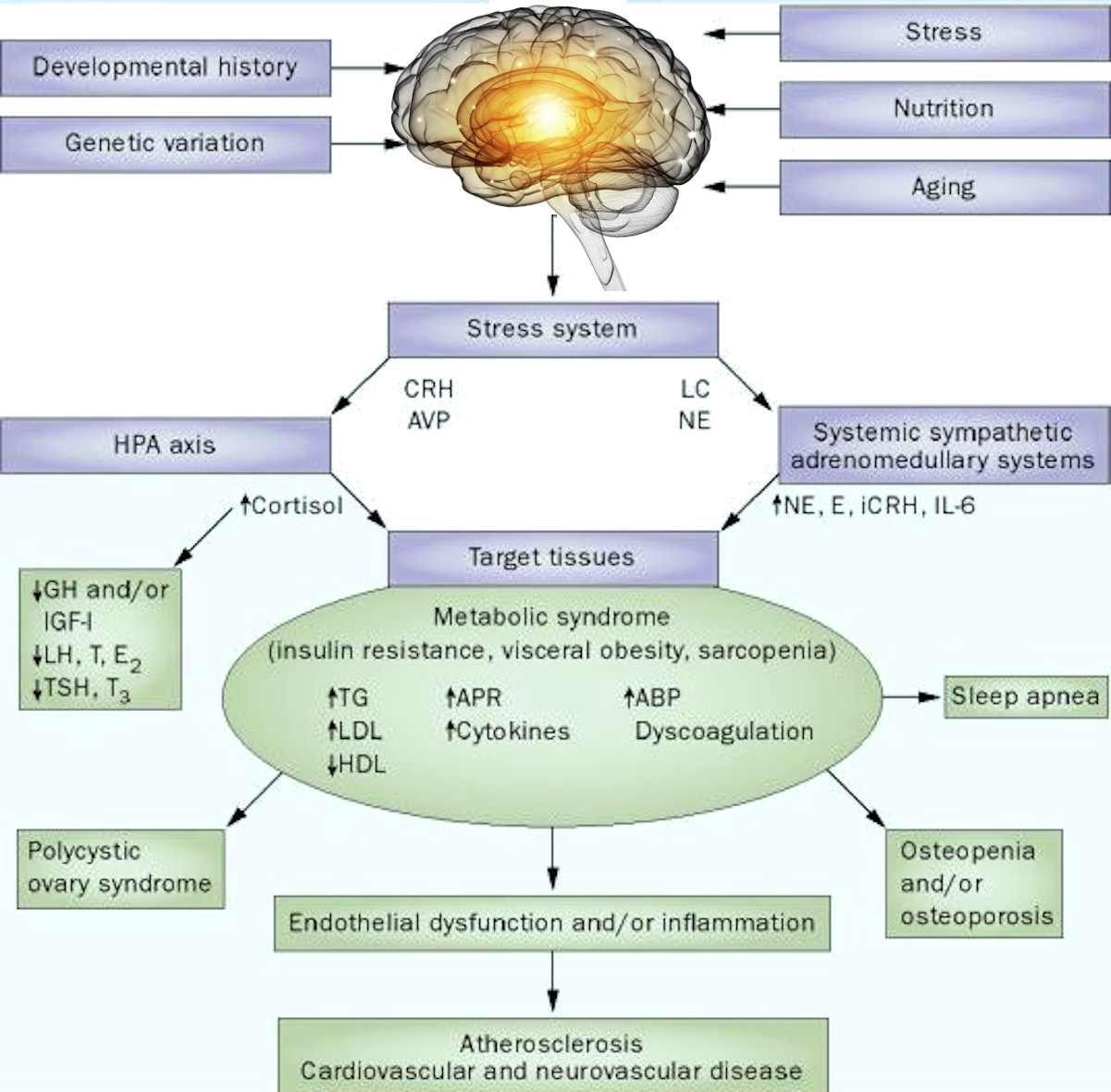

According to current scientific views, infection with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus leads to the development of severe disorders in the immune system. It also causes massive inflammation and microthrombus formation. These and other problems threaten the patient’s life. Now, scientists are trying to understand why they arise and prevent their development.

Megan Stanifer, a researcher at the University of Heidelberg (Germany), leads molecular biologists. They uncovered the coronavirus’s unexpected effect on the human innate immune system and intestines. They studied how its particles multiplied in a “dummy” intestinal tissue, repeating the small intestine structure ileum.

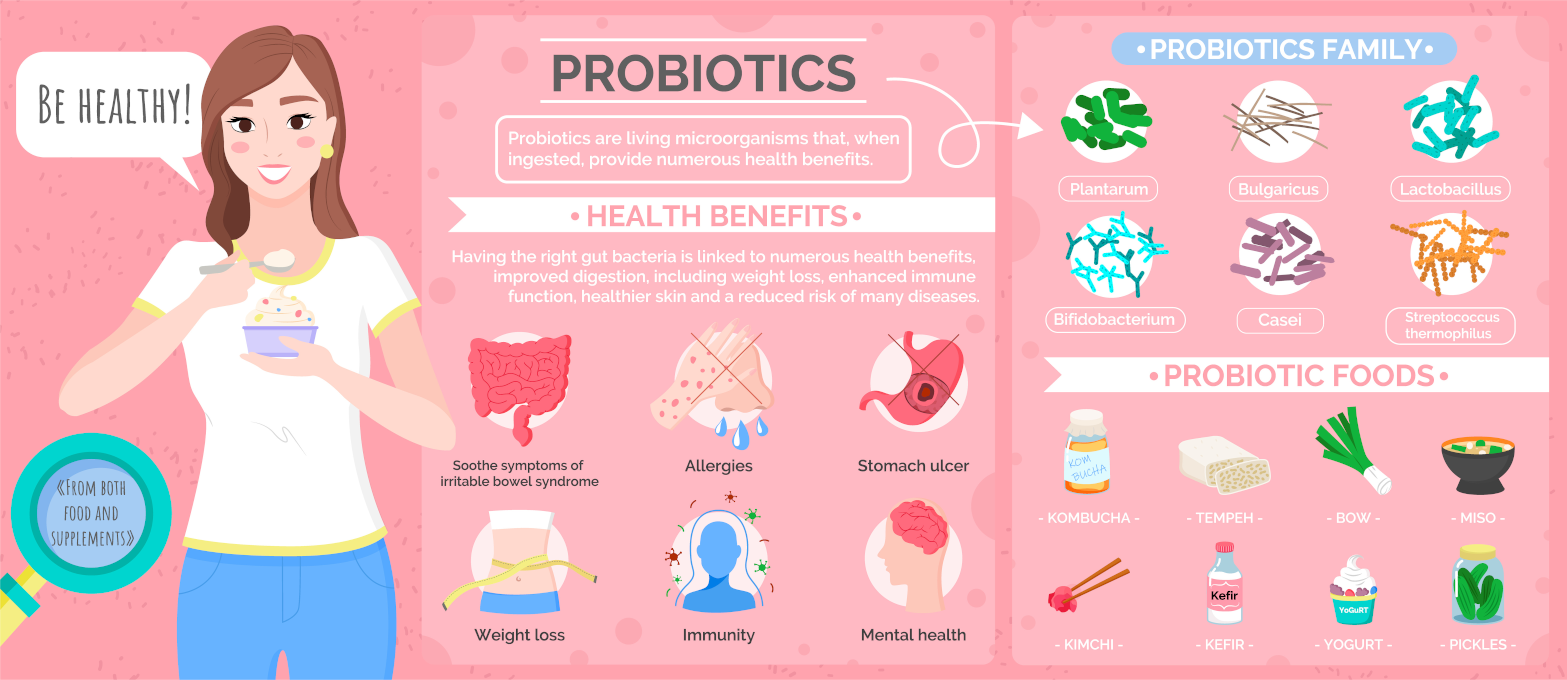

Probiotic implant and alkalising colonic with bicarbonate of soda

Alkalising colonic irrigation with bicarbonate of soda and high strength probiotic implants and comprehensive consultation is available at Parkland Natural Health Clinic.

The coronavirus shuts down several genes.

First, scientists were interested in what types of intestinal cells SARS-CoV-2 infects and what consequences the virus’s penetration into these bodies leads to. To do this, scientists isolated single cells from a human-made analogue of intestinal tissue. They also deciphered the structure of the RNA molecules in them, comparing them with chains of a similar kind present in healthy cells.

Initially, biologists expected to find the dependence of the probability of infection. The number of affected cells should be on the level of activity of the ACE2 gene. The coronavirus uses it to penetrate lung tissue. Unexpectedly, these expectations did not come true. The probability of infection and the number of infected intestinal cells did not depend on how many ACE2 receptors were present on their surface.

Moreover, subsequent observations indicated that the virus’s penetration led to the opposite. That is, the activity of this gene decreased, the reasons for which are not yet clear. The virus penetration led to the shutdown of several genes associated with the reaction of cells to interferons. Interferons are complex protein molecules that are simultaneously capable of neutralizing viral particles. At the same time, they activate immunity in already infected and healthy cells.

A similar feature of SARS-CoV-2 allows this virus to multiply in the intestine for a very long time. It also allows it to penetrate other regions of the body. Moreover, it creates favourable conditions for its existence in the digestive system. Stanifer and her colleagues will continue observations of how the virus replicates in the intestines of animals. They hope it will help scientists understand how this process plays a role in developing COVID-19.

Back and chest waxing

Back and chest waxing combines hair removal on two large areas of the male body. Our specialists will be happy to be of some help to you. This treatment lasts sixty minutes.